Contributed by Eddie Becker

1619

The other crucial event that would

play a role in the development of America was the arrival of Africans to

Jamestown. A Dutch slave trader exchanged his cargo of Africans for food in

1619. The Africans became indentured servants, similar in legal position to

many poor Englishmen who traded several years labor in exchange for passage to

America. The popular conception of a racial-based slave system did not develop

until the 1680's. (A Brief

History of Jamestown, The Association for the Preservation of Virginia

Antiquities, Richmond, VA 23220, email:

apva@apva.org, Web published February, 2000)

The legend has been repeated endlessly that the first blacks in Virginia were "indentured servants," but there is no hint of this in the records. The legend grew up because the word slave did not appear in Virginia records until 1656, and statutes defining the status of blacks began to appear casually in the 1660s. The inference was then made that blacks called servants must have had approximately the same status as white indentured servants. Such reasoning failed to notice that Englishmen, in the early seventeenth century, used the work servant when they meant slave in our sense, and, indeed, white Southerners invariably used servant until 1865 and beyond. Slave entered the Southern vocabulary as a technical word in trade, law and politics. (Robert McColley in Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery, Edited by Randall M. Miller and John David Smith, Greenwood Press, 1988 pp 281)

Jamestown had exported 10 tons of tobacco to Europe and was a boomtown. The export business was going so well the colonists were able to afford two imports which would greatly contribute to their productivity and quality of life. 20 Blacks from Africa and 90 women from England. The Africans were paid for in food; each woman cost 120 pounds of tobacco. The Blacks were bought as indentured servants from a passing Dutch ship low on food, and the women were supplied by a private English company. Those who married the women had to pay their passage--120 pounds of tobacco. (Gene Barios, Tobacco BBS: tobacco news )

With the success of tobacco planting, African Slavery was legalized in Virginia and Maryland, becoming the foundation of the Southern agrarian economy. (The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia, 1995 by Columbia University Press from MS Bookshelf.)

Although the number of African American slaves grew slowly at first, by the 1680s they had become essential to the economy of Virginia. During the 17th and 18th centuries, African American slaves lived in all of England’s North American colonies. Before Great Britain prohibited its subjects from participating in the slave trade, between 600,000 and 650,000 Africans had been forcibly transported to North America. ("Immigration," Microsoft Encarta 98 Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation.)

Following the arrival of twenty Africans aboard a Dutch man-of-war in Virginia in 1619, the face of American slavery began to change from the "tawny" Indian to the "blackamoor" African in the years between 1650 and 1750. Though the issue is complex, the unsuitability of Native Americans for the labor intensive agricultural practices, their susceptibility to European diseases, the proximity of avenues of escape for Native Americans, and the lucrative nature of the African slave trade led to a transition to an African based institution of slavery. During this period of transition, however, the colonial "wars" against the Pequots, the Tuscaroras, the Yamasees, and numerous other Indian nations led to the enslavement and relocation of tens of thousands of Native Americans. In the early years of the eighteenth century, the number of Native American slaves in areas such as the Carolinas may have been as much as half of the African slave population. During this transitional period, Africans and Native Americans shared the common experience of enslavement. In addition to working together in the fields, they lived together in communal living quarters, produced collective recipes for food and herbal remedies, shared myths and legends, and ultimately became lovers. The intermarriage of Africans and Native Americans was facilitated by the disproportionality of African male slaves to females (3 to 1) and the decimation of Native American males by disease, enslavement, and prolonged wars with the colonists.

As Native American societies in the Southeast were primarily matrilineal, African males who married Native American women often became members of the wife's clan and citizens of the respective nation. As relationships grew, the lines of distinction began to blur. The evolution of red-black people began to pursue its own course; many of the people who came to be known as slaves, free people of color, Africans, or Indians were most often the product of integrating cultures. In areas such as Southeastern Virginia, The Low Country of the Carolinas, and Silver Bluff, S.C., communities of Afro-Indians began to spring up. The depth and complexity of this intermixture is revealed in a 1740 slave code in South Carolina: all Negroes and Indians, (free Indians in amity with this government, and Negroes, mulattos, and mustezoes, who are now free, excepted) mulattos or mustezoes who are now, or shall hereafter be in this province, and all their issue and offspring...shall be and they are hereby declared to be, and remain hereafter absolute slaves. (Patrick Minges, Beneath the Underdog: Race, Religion and the "Trail of Tears" Union Seminary Quarterly Review Email: pm47@columbia.edu Union Theological Seminary, New York )

Millions of Native Americans were also enslaved, particularly in South America. In the American colonies in 1730, nearly 25 percent of the slaves in the Carolinas were Cherokee, Creek, or other Native Americans. From the 1500s through the early 1700s, small numbers of white people were also enslaved by kidnapping, or for crimes or debts. SUGGESTED READINGS: Herbert Klein's, African Slavery in Latin American and the Caribbean (1986); Ramon Gutierrez's When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico 1500-1846 (1991); Great Documents in American Indian History (1995), edited by Wayne Moquin; J. McIver Weatherford's Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America (1991); Native Heritage: Personal Accounts by American Indians 1790-Present (1995), edited by Arlene Hirschfelder; Robert Edgar Conrad's Children of God's Fire: A Documentary History of Black Slavery in Brazil (1983); and Sidney Mintz's and Richard Price's An Anthropological Approach to the Afro-American Past: A Caribbean Perspective (1981). (Ten Myths, Half-truths and Misunderstandings about Black History, Ethnic NewsWatch SoftLine Information, Inc., Stamford, CT) ( For more information about the history of the contact between Native Americans, Africans and Americans of African descent, see the work done by Patrick Minges, Union Theological Seminary )

Also see: Winthrop Jordan's White Over Black_ (see the index to find the relevant pages), and in an old publication by Almon Wheeler Lauber called Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States, Columbia University Studies in History, Economics, and Public Law, Columbia University, 1913

In the Americas, there were added dimensions to this resistance, especially reactions to the racial characteristics of chattel slavery. This fundamental difference from the condition of slaves in Africa emerged gradually, although the roots of racial categories were established early. Acts of resistance that combined indentured Irish workers, African slaves, and Amer-Indian prisoners did occur, although in the end these alliances disintegrated. Furthermore, slaves did not consolidate ethnic identifications on the basis of color, but it was widely understood that most blacks were slaves and no slaves were white. Although there were black, mulatto and American-born slave owners in some colonies in the Americas, and many whites did not own slaves, chattel slavery was fundamentally different in the Americas from other parts of the world because of the racial dimension. (Hilary McD. Beckles, "The Colors of Property: Brown, white and Black Chattels and their Responses to the Colonial Frontier", Slavery and Abolition, 15, 2 (1994), 36-51. Cited by Paul E. Lovejoy in "The African Diaspora: Revisionist Interpretations of Ethnicity, Culture and Religion under Slavery" . Studies in the World History of Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, II, 1 (1997))

Tobacco was considered powerful medicine by native Americans. Cigarettes of today have been adulterated to enhance their addictive properties. Though ritual varied, "Smoking [by native Americans] was chiefly done after the evening meal, in the sweathouse, before going to sleep. It was a social ritual, and the pipes were passed around the group. A man never let his pipe out of his sight. Occasionally he would stop for a smoke when on a journey or when meeting someone on the trail." (Early Uses of Indian Tobacco in California, California Natural History Guides: 10, Early Uses Of California Plants, By Edward K. Balls, University Of California Press, Copyright 1962 by the Regents of the University of California ISBN: 0-520-00072-2 )

In fact, the first twenty "Negar" slaves had arrived from the West Indies in a Dutch vessel and were sold to the governor and a merchant in Jamestown in late August of 1619, as reported by John Rolfe to John Smith back in London. (Robinson, Donald L. Slavery and the Structure of American Politics, 1765 - 1820. NY: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, 1971) By 1625, ten slaves were listed in the first census of Jamestown. The first public slave auction of 23 individuals, disgracefully, was held in Jamestown square itself in 1638. What were to become the parameters and properties of the "peculiar institution" were defined in the Virginia General Assembly from about 1640 onwards. Negro indenture, then, appears to have been no more than a legal fiction of brief duration in Virginia. Black freedmen would live in a legal limbo until the general emancipation in 1864, unable to stand witness in their own defense against the testimony of any Euro-American. The General Court dispositions that appear after 1640 seem to support this contention. Barbados was the first British possession to enact restrictive legislation governing slaves in 1644, and other colonial administrations, especially Virginia and Maryland, quickly adopted similar rules modeled on it. Whipping and branding, borrowed from Roman practice via the Iberian-American colonies, appeared early and with vicious audacity.

One Virginian slave, named Emanuel, was convicted of trying to escape in July, 1640, and was condemned to thirty stripes, with the letter "R" for "runaway" branded on his cheek and "work in a shackle one year or more as his master shall see cause." . (Robinson, Donald L. Slavery and the Structure of American Politics, 1765 - 1820. NY: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, 1971) Shades of Rome! This was most certainly not a contractually obligated indentured servant, however oppressed but consistent with English common law, that could expect release from his contract after a time. Rather, this was an abject slave, subject to the court's definition of him as mercantable and movable "property," as chattel or res, and to his master's virtual whim. Indeed, the general assembly of Virginia in 1662 passed an act which directly and consciously invoked Justinian code: partvs seqvitvr ventram, whereby a child born of a slave mother was also held to be a slave, regardless of its father's legal status. (Greene, Lorenzo Johnston. The Negro in Colonial New England. NY: Athaneum Press, 1971) A few years later, the population of Africans in bondage in Virginia reached about 2,000, and another statute (1667) established compulsory life servitude, de addictio according to Roman code, for Negroes ... slavery had become an official institution. (Whitefield, Theodore Marshall. Slavery Agitation in Virginia, 1829 - 1832. NY : Negro Universities Press, 1930 Securing the Leg Irons: Restriction of Legal Rights for Slaves in Virginia and Maryland, 1625 - 1791. Slavery In Early America's Colonies-- Seeds of Servitude Rooted in The Civil Law of Rome by Charles P.M. Outwin)

1620

The Pilgrims settled at Plymouth

Massachusetts. ". Plymouth, for the most part, had servants and not slaves,

meaning that most black servants were given their freedom after turning 25

years old--under similar contractual arrangement as English apprenticeships."

(Were there any blacks on the

Mayflower? By Caleb Johnson member of the General Society of Mayflower

Descendants)

1624

New Amsterdam- The Dutch, who had

entered the slave trade in 1621 with the formation of the Dutch West Indies

Co., import blacks to serve on Hudson Valley farms. According to Dutch law, the

children of manumitted (freed) slaves are bound to slavery. (Chronology: A Historical Review, Major Events in Black History

1492 thru 1953 by Roger Davis and Wanda Neal-Davis)

1638

The price tag for an African male

was around $27, while the salary of a European laborer was about seventy cents

per day. (Willie F. Page. _The Dutch Triangle: The

Netherlands and the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1621-1664_. Studies in African

American History and Culture. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997. xxxv + 262

pp. Bibliographical referen1ces and index. $66.00 (cloth), ISBN 0-8153-2881-8.

Reviewed for H-Review by Dennis R.

Hidalgo , Central Michigan University)

1640

Whipping and branding, borrowed

from Roman practice via the Iberian-American colonies, appeared early and with

vicious audacity. One Virginian slave, named Emanuel, was convicted of trying

to escape in July, 1640, and was condemned to thirty stripes, with the letter

"R" for "runaway" branded on his cheek and "work in a shackle one year or more

as his master shall see cause." Charles P.M. Outwin, Securing the Leg Irons:

Restriction of Legal Rights for Slaves in Virginia and Maryland, 1625 –

1791, footnote taken from Catterall, Helen Honor Tunnicliff. Judicial Cases

Concerning American Slavery and the Negro, vol. I, Cases from the Courts of

England, Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky, and vol. IV, Cases from the

Courts of New England, the Middle States, and the District of Columbia.

Washington, D. C., Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1926 & 1936. Page

77)

1641

Massachusetts colony legalizes

slavery. (Underground Railroad Chronology, National Park

Service,

http://www.nps.gov/boaf/urrtim~1.htm)

1642

Virginia colony enacts law to

fine those who harbor or assist runaway slaves.

(Underground Railroad Chronology, National Park

Service). The Virginia law, penalizes people sheltering runaways

20 pounds worth of tobacco for each night of refuge granted. Slaves are branded

after a second escape attempt. (African American History,

Chronology: A Historical Review Major Events in Black

History 1492 thru 1953 )

1649

Black laborers in the Virginia

colony still number only 300 (see 1619; 1671). (The People's

Chronology 1995, 1996 by James Trager from MS Bookshelf)

Tobacco exports bring prosperity to the Virginia colony.(The People's Chronology 1995, 1996 by James Trager from MS Bookshelf)

1650 For centuries the issue of equal rights presented a major challenge to the state. Virginia, after all, had been the primary site for the development of black slavery in the Americas. By the 1650s some of the indentured servants had earned their freedom. Because replacements, whether black or white, were in limited supply and more costly, the Virginia plantation owners considered the advantages of the "perpetual servitude" policy exercised by Caribbean landowners. Following the lead of Massachusetts and Connecticut, Virginia legalized slavery in 1661. In 1672 the king of England chartered the Royal African Company to bring the shiploads of slaves into trading centers like Jamestown, Hampton, and Yorktown. (Compton's Encyclopedia Online. http://www.comptons.com/encyclopedia/)

1650

For centuries the issue of equal

rights presented a major challenge to the state. Virginia, after all, had been

the primary site for the development of black slavery in the Americas. By the

1650s some of the indentured servants had earned their freedom. Because

replacements, whether black or white, were in limited supply and more costly,

the Virginia plantation owners considered the advantages of the "perpetual

servitude" policy exercised by Caribbean landowners. Following the lead of

Massachusetts and Connecticut, Virginia legalized slavery in 1661. In 1672 the

king of England chartered the Royal African Company to bring the shiploads of

slaves into trading centers like Jamestown, Hampton, and Yorktown.

(Compton's

Encyclopedia Online.)

1650

World population estimated 500

million. (GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS

1994/1995 Leading Edge Research Group)

1651

Thomas Hobbes, in Leviathan,

argued from a mechanistic theory that man is a selfishly individualistic animal

at constant war with others. In the state of nature, life is "nasty, brutish,

and short." (www.sciencetimeline.net presents,

marks in the evolution of western thinking about nature, Assembled by

David Lee,

http://www.sciencetimeline.net/1651.htm)

1660

Slavery spread quickly in the

American colonies. At first the legal status of Africans in America was poorly

defined, and some, like European indentured servants, managed to become free

after several years of service. From the 1660s, however, the colonies began

enacting laws that defined and regulated slave relations. Central to these laws

was the provision that black slaves, and the children of slave women, would

serve for life. This premise, combined with the natural population growth among

the slaves, meant that slavery could survive and grow…("Slavery in the United States," Microsoft Encarta 98

Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation.)

The continuing demand for African slaves' labor arose from the development of plantation agriculture, the long-term rise in prices and consumption of sugar, and the demand for miners. Not only did Africans represent skilled laborers, but they were also experts in tropical agriculture. Consequently, they were well-suited for plantation agriculture. The high immunity of Africans to malaria and yellow fever compared with Europeans and the indigenous peoples made them more suitable for tropical labor. While white and red labor were used initially, Africans were the final solution to the acute labor problem in the New World. (The Economics of the African Slave Trade, By Anika Francis, The March 1995 Issue of The Vision Online, http://dolphin.upenn.edu/~vision/vis/Mar-95/5284.html)

Slaves were mostly for sugar plantations, diamond mines in Brazil, house servants, on tobacco farms in Virginia, in gold mines in Hispaniola and later the cotton industry in the Southern States of the USA. "The hybridization of sugar cane between the sixteenth and the nineteenth century made increasingly large harvests possible." M.E. Descoutilz: Flore pittoresque et medicale des Antilles. (Vol.4. Paris, 1883) (KURA HULANDA Museum, Curaçao, http://www.kurahulanda.com/site/museum/museum.html))

Despite this growth in tobacco production, problems in price-stability and quality existed. In 1660, when the English markets became glutted with tobacco, prices fell so low that the colonists were barely able to survive. In response to this, planters began mixing other organic material, such as leaves and the sweepings from their homes, in with the tobacco, as an attempt to make up by quantity what they lost by low prices. The exporting of this trash tobacco solved the colonists' immediate cash flow problems, but accentuated the problems of overproduction and deterioration of quality.[8] As the reputation of colonial tobacco declined, reducing European demand for it, colonial authorities stepped in to take corrective measures. During the next fifty years they came up with three solutions. First, they reduced the amount of tobacco produced; second, they regularized the trade by fixing the size of the tobacco hogshead and prohibiting shipments of bulk tobacco; finally, they improved quality by preventing the exportation of trash tobacco. These solutions soon fell through because there was no practical way to enforce the law. It was not until 1730, when the Virginia Inspection Acts were passed, that tobacco trade laws were fully enforced (Middleton, Arthur Pierce. Tobacco Coast. Newport News, Virginia: Mariners' Museum, 1953.. P. 112-116, Finlayson, Ann. Colonial Maryland. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson Inc. 1974. P. 66-679. From Economic Aspects of Tobacco during the Colonial Period 1612-1776, On line at http://tobacco.org)

1661

A reference to slavery entered

into Virginia law, and this law was directed at white servants -- at those who

ran away with a black servant. The following year, the colony went one step

further by stating that children born would be bonded or free according to the

status of the mother. (Timeline

from the PBS series Africans In America)

1661

Virginia authorities noted that

indentured servants were planning a rebellion and Maryland officials faced a

strike (1663). (Mark

Lause

American

Labor History)

After 1691, freed black slaves were banished from Virginia. (How the Cradle of Liberty Became a Slave-Owning Nation. By Susan DeFord, Special to The Washington Post Wednesday, December 10, 1997; Page H01 (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/contents/))

1662

A Virginia law assumed Africans

would remain servants for life. ." (Slavery in America

Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1995)

Citing 1662 Virginia statute providing that "[c]hildren got by an Englishman upon a Negro woman shall be bond or free according to the condition of the mother". Throughout the late 17th and early 18th century, several colonial legislatures adopted similar rules which reversed the usual common law presumptions that the status of the child was determined by the father. (See id. at 128 (citing 1706 New York statute); id. at 252 (citing a 1755 Georgia Law)). These laws facilitated the breeding of slaves through Black women's bodies and allowed for slaveholders to reproduce their own labor force. (See PAULA GIDDINGS, WHEN AND WHERE I ENTER: THE IMPACT OF BLACK WOMEN ON RACE AND SEX IN AMERICA 37 (1984) (noting that "a master could save the cost of buying new slaves by impregnating his own slave, or for that matter, having anyone impregnate her"). For a discussion of Race and Gender see Cheryl I. Harris, Myths of Race and Gender in the Trials of O.J. Simpson and Susan Smith -- Spectacles of Our Times)

It was conventional wisdom in the South that the best way to get a good house servant was to raise one. Often, children were taken from their parents to sleep in the Big House as well as to eat, work and play there. Their families were replaced by the families of their owners, with their position in those families clearly defined. ("A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women In America", by Darlene Clark Hine and Kathleen Thompson p 70, cited in TheBlackMarket.com FAQ)

The Laws of Virginia (1662, 1691, 1705) These statutes chart the development of regulations on the sexual and reproductive lives of indentured servants and slaves, the growing institutionalization of slavery, and the construction of racism. Note the increasingly harsh penalties and how punishments differed by gender. (To view the laws visit America Past and Present On Line)

The first known Virginia statute punishing interracial sexual relations was enacted in 1662. Act XII, 2 Laws of Va. 170, 170 (Hening 1823) (enacted 1662), cited in, Leon Higginbotham, Jr. and Barbara K. Kopytoff, Racial Purity and Interracial Sex in the Law of Colonial and Antebellum Virginia, 77 Geo. L.J. 1967 (1989); supra, at 1993. As early as 1691, Virginia had enacted a statute punishing interracial marriage. Act XVI, Laws of Va. 86, 86-87 (Hening 1812) (enacted 1691), cited in, Higginbotham, supra, at 1995. The antimiscegenation laws and prohibitions were the legal manifestations of an often violently enforced taboo against sexual relations between white women and black men. The punishment in 1691 for marriage between an English or white individual and a black, mulatto, or Indian was banishment and removal from Virginia forever. Id. (The last antimiscegenation laws in Virginia were overturned in 1967). (UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, v. NORWOOD W. BARBER, (CR-92-30024) Decided: April 5, 1996)

Slavery in the United States was governed by an extensive body of law developed from the 1660s to the 1860s. Every slave state had its own slave code and body of court decisions. All slave codes made slavery a permanent condition, inherited through the mother, and defined slaves as property, usually in the same terms as those applied to real estate. Slaves, being property, could not own property or be a party to a contract. Since marriage is a form of a contract, no slave marriage had any legal standing. All codes also had sections regulating free blacks, who were still subject to controls on their movements and employment and were often required to leave the state after emancipation. (American Treasures of the Library of Congress: MEMORY, Slavery in the Capitol, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trm009.html)

Slaves charged with crimes in Virginia were tried in special non-jury courts created in 1692. The purpose of the courts was not to guarantee due process but to set an example speedily. "Those slaves who attacked white people or property usually acted with a purpose and not just on impulse," wrote Philip J. Schwarz, a Virginia Commonwealth University professor who has studied slave courts. "Many killings, poisonings, thefts, uses of arson and attempts to rebel were efforts to oppose the means of maintaining slavery." The courts could resort to hideous punishments to reassert white authority. Offending slaves were hung, burned at the stake, dismembered, castrated and branded in addition to the usual whippings. White fear of black rebellion was a constant undercurrent. (How the Cradle of Liberty Became a Slave-Owning Nation. By Susan DeFord, Special to The Washington Post Wednesday, December 10, 1997; Page H01 http://www.washingtonpost.com)

1663

Maryland Settlers pass law

stipulating that all imported blacks are to be given the status of slaves. Free

white women who marry black slaves are to be slaves during the lives of their

spouses, Ironically, children born of white servant women and blacks are

regarded as free by a 1681 law. (The Negro Almanac a

reference work on the Afro American, compiled and edited by harry A Ploski, and

Warren Marr, II. Third Edition 1978 Bellwether Publishing)

1663/09/13

First serious recorded slave

conspiracy in Colonial America takes place in Virginia. A servant betrayed plot

of white servants and Negro slaves in Gloucester County, Virginia.

(Major Revolts and Escapes, Lerone Bennett, Before the

Mayflower, http://www.afroam.org/history/slavery/revolts.html)

1664

Slavery sanctioned by law; slaves

to serve for life. (MD info from Maryland A Chronology &

Documentary Handbook, 1978 Oceana Publications, Inc. And

Maryland

Historical Chronology )

1664

Maryland passes a law making

lifelong servitude for black slaves mandatory to prevent them from taking

advantage of legal precedents established in England which grant freedom under

certain conditions, such as conversion to Christianity. Similar laws are later

passed in New York, New Jersey, the Carolinas and Virginia. (The History Place,

Early

Colonial Era Beginnings to 1700 Chronology)

1664

Slavery introduced into law in

Maryland, the law also prohibited marriage between white women and black men.

This particular act remained in effect for over 300 years, and between 1935 and

1967 the law was extended to forbid the marriage of Malaysians with blacks or

whites. The law was finally repealed in 1967. (Maryland

State Archive, THE ARCHIVISTS' Record Series of the Week, Phebe Jacobsen

"Colonial Marriage Records" Bulldog Vol. 2, No. 26 18

July

1988)

There had been a number of marriages between white women and slaves by 1664 when Maryland passed a law which made them and their mixed-race children slaves for life, noting that "divers freeborne English women forgettfull of their free Condicon and to the disgrace of our Nation doe intermarry with Negro Slaves" [Archives of Maryland, 1:533-34]. (FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS OF MARYLAND AND DELAWAREINTRODUCTION By Paul Heinegg, p.heinegg@worldnet.att.net This is the history of the free African American communities of Maryland and Delaware during the colonial period as told through their family histories. http://www.freeafricanamericans.com/Intro_md.htm) Also see 1681.

Throughout most of the colonial period, opposition to slavery among white Americans was virtually nonexistent. Settlers in the 17th and early 18th centuries came from sharply stratified societies in which the wealthy savagely exploited members of the lower classes. Lacking a later generation's belief in natural human equality, they saw little reason to question the enslavement of Africans. As they sought to mold a docile labor force, planters resorted to harsh, repressive measures that included liberal use of whipping and branding. ("Slavery in the United States," Microsoft Encarta 98 Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation.)

One characteristic which set American slavery apart was its racial basis. In America, with only a few early and insignificant exceptions, all slaves were Africans, and almost all Africans were slaves. This placed the label of inferiority on black skin and on African culture. In other societies, it had been possible for a slave who obtained his freedom to take his place in his society with relative ease. In America, however, when a slave became free, he was still obviously an African. The taint of inferiority clung to him. Not only did white America become convinced of white superiority and black inferiority, but it strove to impose these racial beliefs on the Africans themselves. Slave masters gave a great deal of attention to the education and training of the ideal slave, In general, there were five steps in molding the character of such a slave: strict discipline, a sense of his own inferiority, belief in the master's superior power, acceptance of the master's standards, and, finally, a deep sense of his own helplessness and dependence. At every point this education was built on the belief in white superiority and black inferiority. Besides teaching the slave to despise his own history and culture, the master strove to inculcate his own value system into the African's outlook. The white man's belief in the African's inferiority paralleled African self hate. (Norman Coombs, The Immigrant Heritage of America, Twayne Press, 1972. CHAPTER 3, CHAPTER 3, The Shape of American Slavery).

The psychological impact on the individual of slavery contrasted to that of individuals who survived the Nazi holocaust, In Stanley M. Elkins thinking, the concentration camps were a modern example of a rigid system controlling mass behavior. Because some of those who experienced them were social scientists trained in the skills of observation and analysis, they provide a basis for insights into the way in which a particular social system can influence mass character. While there is also much literature about American slavery written both by slaves and masters, none of it was written from the viewpoint of modern social sciences. However, Elkins postulates that a slave type must have existed as the result of the attempt to control mass behavior, and he believes that this type probably bore a marked resemblance to the literary stereotype of "Sambo." Studying concentration camps and their impact on personality provides a tool for new insights into the working of slavery, but, warns Elkins, the comparison can only be used for limited purposes. Although slavery was not unlike the concentration camp in many respects, the concentration camp can be viewed as a highly perverted form of slavery, and both systems were ways of controlling mass behavior

The concentration camp experience began with what has become labeled as shock procurement. As terror was one of the many tools of the system, surprise late-night arrests were the favorite technique. Camp inmates generally agreed that the train ride to the camp was the point at which they experienced the first brutal torture. Herded together into cattle cars, without adequate space, ventilation, or sanitary conditions, they had to endure the horrible crowding and the harassment of the guards. When they reached the camp, they had to stand naked in line and undergo a detailed examination by the camp physician. Then, each was given a tag and a number. These two events were calculated to strip away one's identity and to reduce the individual to an item within an impersonal system. (for critic of Stanley M. Elkins see Norman Coombs, The Immigrant Heritage of America, Twayne Press, 1972. CHAPTER 3, Slavery and the Formation of Character and Slavery, The Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life, by Stanley M. Elkins. University of Chicago)

"Two days before embarkation, the head of every male and female is neatly shaved; and, if the cargo belongs to several owners, each man's brand is impressed on the body of his irrespective Negro. This operation is performed with pieces of silver wire, or small irons fashioned into the merchant's initials, heated just hot enough to blister without burning the skin. When the entire cargo is the venture of but one proprietor, the branding is always dispensed with. "On the appointed day, the barracoon or slave-pen is made joyous by the abundant 'feed' which signalizes the negro's last hours in his native country. The feast over, they are taken alongside the vessel in canoes; and as they touch the deck, they are entirely stripped, so that women as well as men go out of Africa as they came into it-naked. This precaution, it is understood, is indispensable; for perfect nudity, during the whole voyage, is the only means of securing cleanliness and health. In this state they are immediately ordered below, the men to the hold and the women to the cabin, while boys and girls are, day and night, kept on deck, where their sole protection from the elements is a sail in fair weather, and a tarpaulin in foul. "At meal time they are distributed in messes of ten. Thirty years ago, when the Spanish slave trade was lawful, the captains were somewhat ceremoniously religious than at present, and it was then a universal habit to make the gangs say grace before meat, and give thanks afterwards. In our days, however, they dispense with this ritual… This over, a bucket of salt water is served to each mess by way of 'finger glasses' for the ablution of hands, after which a kidd-either of rice, farina, yams, or beans-according to the tribal habit of the negroes, is placed before the squad. In order to prevent greediness or inequality in the appropriation of nourishment, the process is performed by signals from a monitor, whose motions indicate when the darkies shall dip and when they shall swallow." (Debow's review, Agricultural, commercial, industrial progress and resources./ vol. 18, iss. 3, Mar 1855, New Orleans, The African Slave Trade (pp. 297-305) )

"At sundown, the process of stowing the slaves for the night is begun. The second mate and boatswain descend into the hold, whip in hand, and range the slaves in their regular places; those on the right side of the vessel facing forward, and lying in each other's lap, while those on the left are similarly stowed with their faces towards the stern. In this way each negro lies on his right side, which is considered preferable for the action of the heart. In allotting places, particular attention is paid to size, the taller being selected for the greatest breadth of the vessel, while the shorter and younger are lodged near the bows. When the cargo is large and the lower deck crammed, the supernumeraries are disposed of on deck, which is securely covered with boards to shield them from moisture. The strict discipline of nightly stowage is, of course, of the greatest importance in slavers, else every negro would accommodate himself as if he were a passenger. "In order to insure perfect silence and regularity during night, a slave is chosen as constable from every ten, and furnished with a 'cat' to enforce commands during his appointed watch. In remuneration for his services, which, it may be believed, are admirably performed whenever the whip is required, he is adorned with an old shirt or tarry trousers. Now and then, billets of wood are distributed among the sleepers, but this luxury is never granted until the good temper of the negroes is ascertained, for slaves have often been tempted to mutiny by the power of arming themselves with these pillows from the forest." (Debow's review, Agricultural, commercial, industrial progress and resources./ vol. 22, iss. 6, June 1857, New Orleans, The Middle Passage; or, Suffering of Slave and Free Immigrants: pp 570-583 )

Even the most abstract ideals of the [German] SS, such as their intense German nationalism and anti-Semitism, were often absorbed by the old [concentration camp] inmates-a phenomenon observed among the politically well-educated and even among the Jews themselves. The final quintessence of all this was seen in the "Kapo" the prisoner who had been placed in a supervisory position over his fellow inmates. These creatures, many of them professional criminals, not only behaved with slavish servility to the SS, but the way in which they often out did the SS in sheer brutality became one of the most durable features of the concentration-camp legend. (Slavery, The Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life, by Stanley M. Elkins. University of Chicago, first 1959 third edition 1976 page 113 see also Bettelheim, "Individual and Mass Behavior," and Elie Cohen, "Human Behavior," pp. 18p-93, for a discussion of anti-Semitism among the Jews".)

When the vessels arrive at their destined port, the Negroes are again exposed naked to the eyes of all that flock together, and the examination of their purchasers. Then they are separated to the plantations of their several masters, to see each other no more. Here you may see mothers hanging over their daughters, bedewing their naked breasts with tears, and daughters clinging to their parents, till the whipper soon obliges them to part. And what can be more wretched than the condition they then enter upon? Banished from their country, from their friends and relations for ever, from every comfort of life, they are reduced to a state scarce anyway preferable to that of beasts of burden. In general, a few roots, not of the nicest kind, usually yams or potatoes, are their food; and two rags, that neither screen them from the heat of the day, nor the cold of the night, their covering. Their sleep is very short, their labour continual, and frequently above their strength; so that death sets many of them at liberty before they have lived out half their days. The time they work in the West Indies, is from day-break to noon, and from two o'clock till dark; during which time, they are attended by overseers, who, if they think them dilatory, or think anything not so well done as it should be, whip them most unmercifully, so that you may see their bodies long after wealed and scarred usually from the shoulders to the waist. And before they are suffered to go to their quarters, they have commonly something to do, as collecting herbage for the horses, or gathering fuel for the boilers; so that it is often past twelve before they can get home. Hence, if their food is not prepared, they are sometimes called to labour again, before they can satisfy their hunger. And no excuse will avail. If they are not in the field immediately, they must expect to feel the lash. Did the Creator intend that the noblest creatures in the visible world should live such a life as this? (Thoughts Upon Slavery, John Wesley, Published in the year 1774, John Wesley: Holiness of Heart and Life, 1996 Ruth A. Daugherty)

Africa occupies just over 20 percent of the earth's land surface and has roughly 20 percent of the world's population, but European slave traders in the 17th century and the next will decimate the continent by exporting human chattels and introducing new diseases. (The People's Chronology, 1994 by James Trager from MS Bookshelf.)

The transatlantic slave trade produced one of the largest forced migrations in history. From the early 16th to the mid-19th centuries, between 10 million and 11 million Africans were taken from their homes, herded onto ships where they were sometimes so tightly packed that they could barely move, and sent to a strange new land. Since others died before boarding the ships, Africa's loss of population was even greater. ("Slavery in the United States," Microsoft Encarta 98 Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation.)

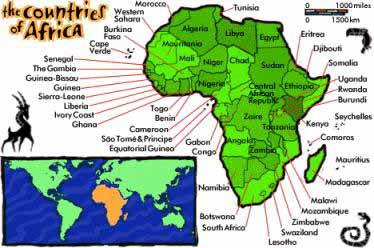

While Ghana was the headquarters of the African slave trade, Tropical America was the real center of the trade. Thirty-six of the forty-two slave fortress were located in Ghana. Aside from Ghana, slaves were shipped from eight coastal regions in Africa including Senegambia, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and Liberia region, Gold Coast, Bight of Benin, Bight of Biafra, Central Africa, and Southeast Africa (from the Cape of Good Hope to the Cape of Delgado, including Madagascar). The slave trade had the greatest impact upon central and western African. According to James Rawley, West Africa supplied 3/5ths of the slaves for exportation between 1701-1810. Half of the slaves were exported to South America, 42% to the Caribbean Islands, 7% to British North America, and 2% to Central America. (The Economics of the African Slave Trade, By Anika Francis, The March Issue of The Vision Online)

The Bight of Biafra was one of the most important sources of enslaved Africans sent to the Americas in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, the forced transport of considerable numbers of Igbo-speaking slaves and others from the interior of the Bight of Biafra across the Atlantic was a central development in the emergence of relatively cohesive ethnic groups in the African diaspora. Igbo, "Moko", "Bibi" and other ethnic groups have been identified in many parts of the Americas, most especially in Jamaica, the tidewater areas of Maryland and Virginia, and other anglophone colonies. Nonetheless, little research has been undertaken to explore the cultural and historical continuities and disjunctures in this population displacement. Moreover the repercussions of the trans-Atlantic slave trade on the interior of the Bight of Biafra during the period of heaviest population displacement in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries remain poorly understood. (Repercussions of the Atlantic Slave Trade: The Interior of the Bight of Biafra and the African Diaspora. Conference to hosted by His Excellency, Governor Chimaroke Nnamini, Enugu State, Nigeria at the Nike Lake Resort, Enugu, Nigeria, July 10-14, 2000. For additional information, contact: Professor Carolyn Brown, Department of History, Rutgers University.)

PROJECTED EXPORTS OF THAT PORTION OF THE FRENCH AND ENGLISH SLAVE TRADE HAVING IDENTIFIABLE REGION OF COAST ORIGIN IN AFRICA, 1711-1810.

- Senegambia (Senegal-Gambia)* 5.8%

- Sierra Leone 3.4%

- Windward Coast (Ivory Coast)* 12.1%

- Gold Coast (Ghana)* 14.4%

- Bight of Benin (Nigeria)* 14.5

- Bight of Biafra (Nigeria)* 25.1%

- Central and Southeast Africa (Cameroon- N.Angola)* 24.7% *

The countries in parentheses are rough approximations to help you find the location on a modern map. "Were these people called by that name during that time in that place?" Excluding some nomadic and semi-nomadic groups.

- SENEGAMBIA: Wolof, Mandingo, Malinke, Bambara, Papel, Limba, Bola, Balante, Serer, Fula, Tucolor

- SIERRA LEONE: Temne, Mende, Kisi, Goree, Kru.

- WINDWARD COAST (incl. Liberia): Baoule, Vai, De, Gola (Gullah), Bassa, Grebo.

- GOLD COAST: Ewe, Ga, Fante, Ashante, Twi, Brong

- BIGHT OF BENIN & BIGHT OF BIAFRA Combined (sorry): Yoruba, Nupe, Benin, Dahomean (Fon), Edo-Bini, Allada, Efik, Ibibio, Ijaw, Ibani,Igbo(Calabar) CENTRAL &

- SOUTHEAST AFRICA: BaKongo, MaLimbo, Ndungo, BaMbo, BaLimbe, BaDongo, Luba, Loanga, Ovimbundu, Cabinda, Pembe, Imbangala, Mbundu, BaNdulunda

Please send comments (see web page below) on whether the following groups should be included as a "Ancestral group" of African Americans, and in what region: Fulani, Tuareg, Dialonke, Massina, Dogon, Songhay, Jekri, Jukun, Domaa, Tallensi, Mossi, Nzima, Akwamu, Egba, Fang, and Ge. (Compid by Kwame Bandele from information in P.D. Curtin's book, "Atlantic Slave Trade" p. 221. http://www.panix.com/~mbowen/sf/faq054.htm)

(Graphic from

Kids Zone, The

countries of Africa and http://library.advanced.org/10320/Tour.htm)

(Graphic from

Kids Zone, The

countries of Africa and http://library.advanced.org/10320/Tour.htm)

In the 1700s the coasts of West Africa had three main divisions controlled by Europeans in their effort to monopolize the slave trade. The three divisions were SENEGAMBIA, UPPER GUINEA, and LOWER GUINEA. SENEGAMBIA'S two navigable rivers, the Senegal and the Gambia, were controlled by the French and the English, respectively. The West Africans who became slaves from the SENEGAMBIA included the Fula, Wolof, Serer, Felup, and the Mandingo. UPPER GUINEA had a two thousand miles coastline from the Gambia south and east to the Bight of Biafra. This coastline was also designated the Windward Coast because of the heavy winds on the shore. The West Africans who became slaves from the UPPER GAMBIA included the Baga and Susu from French Guinea, the Chamba from Sierra Leone, the Krumen from the Grain Coast, and the Fanti and the Ashanti from the Gold Coast, commonly referred to today as Ghana. East of the Volta River was the Slave Coast which was so named because the slave trade was at its height there since the African kings (Slattees) permitted Europeans to compete equally for Africans to become slaves. Those West Africans who became slaves from this region included Yoruban, Ewe, Dahoman, Ibo, Ibibio, and the Efik. LOWER GUINEA had fifteen hundred miles of coastline from Calabar to the southern desert. The West Africans who became slaves from this region were all Bantus. The trading of Africans from the West Coast provided an economic boon for the Europeans. The trading of Africans from the West Coast produced the heinous Middle passage. The trading of Africans from the West Coast produced the African American! (Connections: A Culturally Historical Prospective of West African to African American, by Kelvin Tarrance, Revised: May 3, 1996 http://asu.alasu.edu/academic/advstudies/2b.html)

Slave brokers believed that there were traits of the various African peoples and the preferences of the slave brokers for slaves from specific groups. Colonists always held some view of which tribes produced the most desirable slaves, and this preferred tribal affiliation changed depending on the work and the era. The docile Gold Coast slave was the preferred worker for a while before the Senegambians were elevated to an equal status. The Ashanti were more likely to seek revenge on their oppressor, which put them among the least sought-after tribes. (Margaret Washington's chapter on the Gullahs in Edward Countryman, ed. How Did American Slavery Begin? Boston: St. Martins, 1999. x + 150 pp. Bibliographical references. $35.00 (cloth), ISBN 0-312-21820-6; $11.95 (paper), ISBN 0-312-18261-9. Reviewed for H-Survey by Brian D. McKnight , from H-NET BOOK REVIEW Published by H-Survey@h- net.msu.edu (November, 1999))

Imperial African States that we know about mostly developed along the

Sahel ("Corridor") which was the major trade route between East and West

Africa. The Sahel "shore" was seen as a "coastline" on the great expanse of the

Sahara Desert. (Map found at The Ohio State University

Libraries Black Studies Library Website sources given as Ancient African

Kingdoms, Margaret Shinnie DT25 .S5 1970. A History of the African People,

Robert W. July DT20 .J8 1992, The History Atlas of Africa Samuel Kasule.

G2446.S1 K3 1998 http://aaas.ohio-state.edu/)

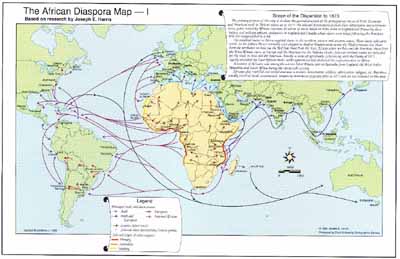

The African Diaspora Map - I This map is the result of almost 20 years research by Joseph Harris, Distinguished Professor, Department of History, Howard University, Washington. The purpose of the map is to show the general direction of the prinicpal sea routes of Arab, European and American trade in African slaves up to 1873. (Mapping Africa, Africa and the Diaspora Movement, The Kennedy Center African Odyssey)

The study of the African component of slave resistance may appear to be the exception to the general state of slave studies, which has tended to pay more attention to the European influences on the Americas rather than the continuities with African history. Palmares is identified as an "African" kingdom in Brazil; an early and important example of the quilombos and palenques of Latin America which also often revealed a strong African link (See the excellent studies in Richard M. Price, ed., Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, 2nd ed. (Baltimore, 1979); Patterson, "Slavery and Slave Revolts," 289-325.) In Jamaica, enslaved Akan are identified with rebellion and marronage; they are considered responsible for setting the course of cultural development among the maroons. (Monica Schuler, "Akan Slave Rebellions in the British Caribbean", Savacou, 1 (1970), 8-31. Also see Mavis C. Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655- 1796 (Trenton, N.J., 1990); and Barbara Klamon Kopytoff, "The Development of Jamaican Maroon Ethnicity," Caribbean Quarterly, 22 (1976), 33-50.) Despite the identification of the ethnic factor, however, most studies of slave resistance fail to examine the historical context in Africa from which these rebellious slaves came. Whether or not there were direct links or informal influences that shaped specific acts of resistance simply has not been determined in most cases.

Because the African background has been poorly understood, perhaps, scholars have tended to concentrate on the European influences which shaped the agenda of slave resistance. Eugene Genovese, for example, has argued that there was a fundamental shift in the patterns of resistance by slaves at the end of the eighteenth century, which he correlated with the French Revolution and the destruction of slavery in St. Domingue. (Eugene D. Genovese, From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World Baton Rouge, 1979). Before the 1790s, according to Genovese, slave resistance tended to draw inspiration from the African past, but the content of that past remains obscure in Genovese's vision. With the spread of revolutionary doctrines in Europe and the Americas, slaves acquired elements of a new ideology that reinforced their resistance to slavery. The process of creolization, which introduced slaves to European thought, brought the actions of slaves more into line with the revolutionary movement emanating from Europe.

Genovese's interpretation further highlights the problem of identifying

the impact of African history on the development of the diaspora. Scholars who

are not well versed in African history seem to have a cloudy image of the

African contribution to resistance and the evolution of slave culture. Perhaps

it is to be expected, therefore, that European influence is more easy to

recognize than African influence. For Genovese, following the earlier lead of

C.L.R. James, (C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint

L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, New York, rev. ed.,

1963). the French Revolution had such an obvious impact on the St.

Domingue uprising that the African dimension is not relevant. As Thornton has

demonstrated, however, even the uprising in St. Domingue had its African

antecedents, especially the legacy of the Kongo civil war. (John K. Thornton, "`I am the Subject of the King of Congo':

African Political Ideology and the Haitian Revolution," Journal of World

History, 4:2 (1993), 181-214) Moreover, influences from Africa

remained a strong force in the struggle against slavery well after the 1790s,

especially in Brazil and Cuba, where there was a continuous infusion of new

slaves from Africa, often from places where slaves had been coming for some

time. The complex blending of African and European experiences undoubtedly

changed over time, but until African history is studied in the diaspora, it

will be difficult to weigh the relative importance of the European and African

traditions. (The African Diaspora: Revisionist

Interpretations of Ethnicity, Culture and Religion under Slavery Paul E.

Lovejoy in Studies in the

World History of Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, II, 1

(1997).) Both images above. Go to URL below

to zoom in on detailed and exact locations. During the 1700s when the Atlantic

slave trade was flourishing, West Africans accounted for approximately

two-thirds of the African captives imported into the Americas. The coastal

ports where these Africans were assembled, and from where they were exported,

are located on this mid-18th-century map extending from present-day Senegal and

Gambia on the northwest to Gabon on the southeast.

Both images above. Go to URL below

to zoom in on detailed and exact locations. During the 1700s when the Atlantic

slave trade was flourishing, West Africans accounted for approximately

two-thirds of the African captives imported into the Americas. The coastal

ports where these Africans were assembled, and from where they were exported,

are located on this mid-18th-century map extending from present-day Senegal and

Gambia on the northwest to Gabon on the southeast.

This decorated and colored map illustrates the dress, dwellings, and work of some Africans. The map also reflects the international interest in the African trade by the use of Latin, French, and Dutch place names. Many of the ports are identified as being controlled by the English (A for Anglorum), Dutch (H for Holland), Danish (D for Danorum), or French (F). Guinea propia, nec non Nigritiae vel Terrae Nigrorum maxima pars . ..Nuremberg: Homann Hereditors, 1743, Hand-colored, engraved map., Geography and Map Division. (http://international.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aopart1.html#0101)

Similar map, of West Africa, 1754. (Not displayed here, but

click

on this URL. Snelgrave voyaged to West Africa as a slaver from 1704 to

1729-30. (Source, William Snelgrave, "A New Map of that Part

of Africa called the Coast of Guinea," in Snelgrave, A New Account of Guinea

(London, 1754).), (Acknowledgement, The John

Carter Brown Library, Brown Univ. (IMAGES OF THE TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE Trade, A

media database compiled by Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr, Presented

by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities)

Similar map, of West Africa, 1754. (Not displayed here, but

click

on this URL. Snelgrave voyaged to West Africa as a slaver from 1704 to

1729-30. (Source, William Snelgrave, "A New Map of that Part

of Africa called the Coast of Guinea," in Snelgrave, A New Account of Guinea

(London, 1754).), (Acknowledgement, The John

Carter Brown Library, Brown Univ. (IMAGES OF THE TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE Trade, A

media database compiled by Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr, Presented

by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities)

Another slave route map is Slave Trade Map of Equatorial Afirca as the piece appeared in the English Abolitionist periodical, The Anti Slavery Reporter and Aborigines Friend, Series IV No. 8-9, 1881-1882 (http://www.ipl.org/ref/timeline/slavemap.htm for details from this map, which shows all of Africa.)

The slave trade from Africa is said to have uprooted as many as 20 million people from their homes and brought them to the Americas. Slavery had existed as a human institution for centuries, but the slaves were usually captives taken in war or members of the lowest class in a society. The black African slave trade, by contrast, was a major economic enterprise. It made the traders rich and brought an abundant labor supply to the islands of the Caribbean and to the American Colonies. (Compton's Encyclopedia Online)

The Methodist theologian, John Wesley, described how slaves were generally procured, carried to, and treated in, America. 1. First. In what manner are they procured? Part of them by fraud. Captains of ships, from time to time, have invited Negroes to come on board, and then carried them away. But far more have been procured by force. The Christians, landing upon their coasts, seized as many as they found, men, women, and children, and transported them to America. It was about 1551 that the English began trading to Guinea; at first, for gold and elephants' teeth; but soon after, for men. In 1556, Sir John Hawkins sailed with two ships to Cape Verd, where he sent eighty men on shore to catch Negroes. But the natives flying, they fell farther down, and there set the men on shore, "to burn their towns and take the inhabitants." But they met with such resistance, that they had seven men killed, and took but ten Negroes. So they went still farther down, till, having taken enough, they proceeded to the West Indies and sold them. 2. It was some time before the Europeans found a more compendious way of procuring African slaves, by prevailing upon them to make war upon each other, and to sell their prisoners. Till then they seldom had any wars; but were in general quiet and peaceable. But the white men first taught them drunkenness and avarice, and then hired them to sell one another. Nay, by this means, even their Kings are induced to sell their own subjects. So Mr. Moore, factor of the African Company in 1730, informs us: "When the King of Barsalli wants goods or brandy, he sends to the English Governor at James's Fort, who immediately sends a sloop. Against the time it arrives, he plunders some of his neighbours' towns, selling the people for the goods he wants. At other times he falls upon one of his own towns, and makes bold to sell his own subjects." So Monsieur Brue says, "I wrote to the King," (not the same,) "if he had a sufficient number of slaves, I would treat with him. He seized three hundred of his own people, and sent word he was ready to deliver them for the goods." He adds: "Some of the natives are always ready" (when well paid) "to surprise and carry off their own countrymen. They come at night without noise, and if they find any lone cottage, surround it and carry off all the people." Barbot, another French factor, says, "Many of the slaves sold by the Negroes are prisoners of war, or taken in the incursions they make into their enemies' territories. Others are stolen. Abundance of little Blacks, of both sexes, are stolen away by their neighbours, when found abroad on the road, or in the woods, or else in the corn-fields, at the time of year when their parents keep them there all day to scare away the devouring birds." That their own parents sell them is utterly false: Whites, not Blacks, are without natural affection! (Thoughts Upon Slavery, John Wesley, Published in the year 1774, John Wesley: Holiness of Heart and Life, 1996 Ruth A. Daugherty)

People have asked why Africans themselves engaged in the slave trade. Given the function of slavery in African societies, the origin of their participation is not too difficult to understand.

First and foremost, slavery was not confused with the notion of superiority and inferiority, a notion later invoked as justification for black slavery in America. On the contrary, it was not at all uncommon for African owners to adopt slave children or to marry slave women, who then became full members of the family. Slaves of talent accumulated property and in some instances reached the status of kings; Jaja of Opobo (in Nigeria) is a case in point. Lacking contact with American slavery, African traders could be expected to assume that the lives of slaves overseas would be as much as they were in Africa; they had no way of knowing that whites in America associated dark colors with sub-human qualities and status, or that they would treat slaves as chattels generation after generation. When Nigeria's Madame Tinubu, herself a slave-trader, discovered the difference between domestic and non-African slavery, she became an abolitionist, actively rejecting what she saw as the corruption of African slavery by the unjust and inhumane habits of its foreign practitioners and by the motivation to make war for profit on the sale of captives. (On Slavery By Femi Akomolafe. 1994, The retrospective history of Africa, Hartford Web Publishing)

The mortality rate among these new slaves ran very high. It is estimated that some five percent died in Africa on the way to the coast, another thirteen percent in transit to the West Indies, and still another thirty percent during the three-month seasoning period in the West Indies. This meant that about fifty percent of those originally captured in Africa died either in transit or while being prepared for servitude. Even this statistic, harsh as it is, does not tell the whole story of the human cost involved in the slave trade. Most slaves were captured in the course of warfare, and many more Africans were killed in the course of this combat. The total number of deaths, then, ran much higher than those killed en route. Many Africans became casualty statistics, directly or indirectly, because of the slave trade. Beyond this, there was the untold human sorrow and misery borne by the friends and relatives of those Africans who were torn away from home and loved ones and were never seen again. (Norman Coombs, The Immigrant Heritage of America, Twayne Press, 1972. CHAPTER 2 The Human Market, The Slave Trade)

It was obvious, however, that the victims of the modern slave trade could not be said to have been acquired directly in war. They had been purchased from African rulers who had seized them in raids whose only purpose had been to acquire this valuable human commodity for the insatiable European market. To this, the advocates of the trade replied by claiming that the Africans purchased by the traders had originally been taken prisoner in "just" wars between Africans. The speciousness of this argument was evident from the beginning. But most slavers accepted what they claimed were African assurances that their human merchandise had indeed been "saved" in a just war, on the principle that it is not up to the purchaser to discover if the goods he is buying have been acquired legitimately or not. In this way slavery remained linked, throughout its 300-year history, to internecine African warfare. Thomas seems to imply that Africans, since they were involved in the trade, must take some measure of the blame for it. This can hardly be denied. What Thomas overlooks, though, is the degree to which the European slave trade contributed to the situation from which it benefited. The abolitionists had always been fully aware of the possible impact of the trade upon Africa. "The slave trade," bewailed Granville Sharp, one of the earliest of the English abolitionists, in 1776, "preyed upon the ignorance and brutality of unenlightened nations, who are encouraged to war with each other for this very purpose." The consequences of this for the continent have only just begun to be examined, but there is sufficient evidence to suggest that at least some of the horrors that modern African rulers continue to inflict upon their peoples, and that African states continue to inflict upon one another, can be linked not only to the disastrous process of de-colonization, but also to the long experience of the European slave trade. Modern slavers were faced with a further problem: religion. (Anthony Pagden he Slave Trade, Review of Hugh Thomas' Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade. The New Republic; 12-22-1997)

"I have no hesitation in saying, that three fourths of the slaves sent abroad from Africa are the fruit of native wars, fomented by the avarice and temptation of our own race. I cannot exculpate any commercial nation from this sweeping censure. We stimulate the negro's passions by the introduction of wants and fancies never dreamed of by the simple native, while slavery was an institution of domestic need and comfort alone. But what was once a luxury has now ripened into an absolute necessity; so that MAN, in truth, has become the coin of Africa, and the 'legal tender' of a brutal trade." (Debow's review, Agricultural, commercial, industrial progress and resources./ vol. 18, iss. 3, Mar 1855, New Orleans, The African Slave Trade (pp. 297-305) )

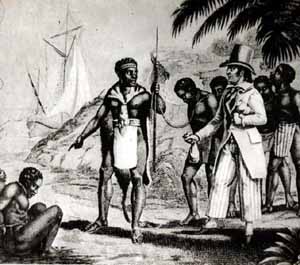

African selling slaves to a European, 19th cent. (?), Source Isabelle Aguet, A Pictorial History of the Slave Trade (Geneva: Editions Minerva, 1971), plate 3, p. 18; from Hull Museums, original source not identified (IMAGES OF THE TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE Trade, A media database compiled by Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr, Presented by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities)

The history of the Atlantic trade in Africa involves

trade routes penetrating deeper and deeper into Africa, in part because people

near the coast learned to defend themselves. Coastal powers like Kongo and

Benin actually lost territory. When a series of slaving states emerged in the

17th and early 18th century, all were in the interior. Oyo was a cavalry state

centered north of the forest. Asante was in the forest but well north of the

coast, able to control trade routes to different colonial forts. Segou was in

western Mali. Futa Jallon was in the mountains of central Guinea. Trade routes

in central Africa also penetrated deep into the heart of Africa. The Matamba of

Queen Nzinga became a valuable trading partner only after it moved from the

coast to a location deep in the interior of Africa. The Igbo developed a

different a kind of trading system, but the largest numbers of slaves probably

came from densely populated areas of central and northern Igboland. Where the

coastal people were successful, it was as middlemen and agents of the trade.

(comments by Martin Klein Re: Gates and African involvement

in the slave trade on the Listserv

Steven Mintz, U. Houston)

The history of the Atlantic trade in Africa involves

trade routes penetrating deeper and deeper into Africa, in part because people

near the coast learned to defend themselves. Coastal powers like Kongo and

Benin actually lost territory. When a series of slaving states emerged in the

17th and early 18th century, all were in the interior. Oyo was a cavalry state

centered north of the forest. Asante was in the forest but well north of the

coast, able to control trade routes to different colonial forts. Segou was in

western Mali. Futa Jallon was in the mountains of central Guinea. Trade routes

in central Africa also penetrated deep into the heart of Africa. The Matamba of

Queen Nzinga became a valuable trading partner only after it moved from the

coast to a location deep in the interior of Africa. The Igbo developed a

different a kind of trading system, but the largest numbers of slaves probably

came from densely populated areas of central and northern Igboland. Where the

coastal people were successful, it was as middlemen and agents of the trade.

(comments by Martin Klein Re: Gates and African involvement

in the slave trade on the Listserv

Steven Mintz, U. Houston)

Africans cooperated with Europeans in the slave trade, and some slaves transported to America were already of the slave class. But most slaves were simply hostages of the trade, and very few were slaves before. A set of political and military circumstances that the Portuguese, the Dutch, and other Europeans imposed on the West Africans forced many African kingdoms to cooperate with the slave trade. Stronger nations had driven many coastal kingdoms from the interior before the arrival of the Europeans. Yet with the coming of European tools and weaponry as payment for African slaves, these coastal kingdoms found themselves in power positions and began slave-raiding expeditions against their former enemies. European slave traders used these rivalries to increase tensions among the African kingdoms for their own mercenary purposes. By fomenting war between kingdoms and by introducing superior arms to those cooperating with the trade, the Europeans obligated many unwilling kingdoms to collaborate with them or face enslavement themselves--raid or be raided. The "most abominable aspect of the slave trade, was fueled by the idea that Africans, even children, were better off Christianized under a system of European slavery than left in Africa amid tribal wars, famines and paganism" (p. 218). (Willie F. Page. _The Dutch Triangle: The Netherlands and the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1621-1664_. Studies in African American History and Culture. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997. xxxv + 262 pp. Bibliographical references and index. $66.00 (cloth), ISBN 0-8153-2881-8. Reviewed for H-Review by Dennis R. Hidalgo, Central Michigan University)

In reality, slavery is an human institution. Every ethnic group has sold members of the same ethnic group into slavery. It becomes a kind of racism; that, while all ethnic groups have sold its own ethnic group into slavery, Blacks can't do it. When Eastern Europeans fight each other it is not called tribalism. Ethnic cleansing is intended to make what is happening to sound more sanitary. What it really is, is White Tribalism pure and simple. The fact of African resistance to European Imperialism and Colonialism is not well known, though it is well documented. Read, for instance, Michael Crowder (ed.), West African Resistance, Africana Publishing Corporation, New York, 1971. Europeans entered Africa in the mid 1400 s and early 1500 s during a time of socio-political transition. Europeans chose a favorite side to win between African nations at a war and supplied that side with guns, a superior war instrument. In its victory, the African side with guns rounded up captives of war who were sold to the Europeans in exchange for more guns or other barter. Whites used these captives in their own slave raids. These captives often held pre-existing grudges against groups they were ordered to raid, having formerly been sold into slavery themselves by these same groups as captives in inter- African territorial wars. In investigating our history and capture, a much more completed picture emerges than simply that we sold each other into slavery. (Did We Sell Each Other Into Slavery? A Commentary by Oscar L. Beard, Consultant in African Studies 24 May 1999 )

The slave trade and the movement of identifiable groups of people have to be tied to specific historical events and processes in Africa, and it must be demonstrated what was and what was not transferred to the Americas. From this perspective, specific historical circumstances determined who was exported and who was not, and these circumstances might well have influenced who was active in promoting adjustments under slavery and preserving knowledge of Africa. The different reasons for enslavement have to be distinguished as crucial variables in determining what factors were important to the enslaved population. Whether an individual became a slave as a result of war, famine, commercial bankruptcy, judicial punishment, or religious persecution mattered. The conscious deportation of political prisoners has to be distinguished from impersonal transactions in the fairs and market-places of Africa. Instances of "mistakes" need to be documented as a means of determining why individuals ended up in the Americas or North Africa who legally should not have been so enslaved. Such examples include arbitrary alterations in the terms and conditions of pawnship, failure to ransom kidnapped victims, and "panyarring", i.e. the seizure of individuals for debt or other compensation. (cf. Toyin Falola and Paul E. Lovejoy (eds.), Pawnship in Africa: Debt Bondage in Historical Perspective (Boulder, 1994). Slaves can be examined as individuals and as recognizable groups of people who had personal and collective histories. (The African Diaspora: Revisionist Interpretations of Ethnicity, Culture and Religion under Slavery Paul E. Lovejoy in Studies in the World History of Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, II, 1 (1997).)

Essay argues that slavery existed and sometimes flourished in Africa before the transatlantic slave trade, but neither the African continent nor persons of African origin were as prominent in the world of slaveholding as they would later become. Second, the capture and sale of slaves across the Atlantic between 1450 and 1850 encouraged expansion and repeated transformation of slavery within Africa, to the point that systems of slavery became central to societies all across the continent. Third, even after the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade (largely accomplished by 1850) and the European conquest of Africa (mostly by 1900), millions of persons remained in slavery in Africa as late as 1930. (For full reading see Slavery in Africa, Microsoft, Encarta, Africana content, 1999 Microsoft Corporation)

But what American Slavery eventually developed into was somewhat unique in several respects. Slavery in other parts of the world had typically involved prisoners of war, and was considered a humane alternative to being put to death. Rarely were the children of those prisoners also placed into slavery. America had not waged a war with Ireland, nor had it waged a war with Africa, or with China. And although it had waged several wars with the Native Americans, they found that Natives made poor slaves and frequently escaped. America was...after all, their homeland...their turf. They knew the land far better than these European upstarts. Many of the Irish came to America voluntarily to escape the horrid economy and famines of their homeland. They choose to be here.

African Slaves were brought to America against the choice. They were kept here against their choice. If they choose to become a part of "America"...they were denied the choice to exercise their full access and full rights within America.

And that choice...is what makes the American Slavery of blacks so unique when compared to most other forms of historical slavery. America was one of the first nations to declare that the rights of the individual were paramount, that "all men were created equal". That a man's freedom to choose was one of his most sacred freedoms. These concepts contrasted radically with the idea that a man could be taken from his home, away from his family, forced to work against his will, and force to breed more people to be borne into the same life.

It is one thing to be a slave, in a land where few even understand what "Freedom" truly is, such as the Sudan (which continues to have slaves even in modern times). But it is a completely different matter to be a slave, in the "Land of the Free". (Debunking Dinesh D'souza's "End of Racism". 1998 F.V. Walton Also read Racism in Modern America for a discussion of modern Racism )

While many slaves were brutalized to the extent that they died without entering into meaningful and sustainable forms of social and cultural interaction with their compatriots, many other slaves more or less successfully re-established communities, reformulated their sense of identity, and reinterpreted ethnicity under slavery and freedom in the Americas. More than simply the foundation for individual and collective acts of resistance, these expressions of agency involved the transfer and adaptation of the contemporary world of Africa to the Americas and were NOT mere "survivals" of some diluted African past. Despite the "social death" of which Orlando Patterson speaks, (Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death, Cambridge, 1982). slaves created a new social world that drew on the known African experience. Certainly the horrors of enslavement, the rough march to coastal ports and the trauma of the Middle Passage affected the psychological and medical health of the enslaved population, but not to the extent imagined by Elkins, at least not in most cases. While their resurrection from Patterson's "social death" was distorted by chattel slavery, many enslaved Africans were none the less fit enough to participate in the "200 Years' War" of which Patterson also writes. (Orlando Patterson, "Slavery and Slave Revolts: A Socio-Historical Analysis of the First Maroon War, Jamaica, 1655-1740", Social and Economic Studies, 19, 3 (1970), 289-325) (From The African Diaspora: Revisionist Interpretations of Ethnicity, Culture and Religion under Slavery Paul E. Lovejoy in Studies in the World History of Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, II, 1 (1997).)

The oppression of European masters and the pull of the international market for primary products may have set the conditions of slaves in the Americas, but in adjusting to these conditions, enslaved Africans nonetheless reinterpreted African issues and modified useful institutions in their quest to make sense out of their conditions and to establish a new identity in the diaspora. This identity began in the context of events and experiences in Africa but over time and after generations evolved into the pan-African identity of Peter Tosh's lyrics: "Anywhere you come from, as long as you're a black man, you're an African". ("African", from Peter Tosh, "Equal Rights", 1977 from The African Diaspora: Revisionist Interpretations of Ethnicity, Culture and Religion under Slavery Paul E. Lovejoy in Studies in the World History of Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, II, 1 (1997).)